|

|

|

|

|

| Issue 31: | Jan. 2026 |

| Essay: | 2,947 words |

| + Footnotes: | 1,777 words |

Essay and Visual Artworks

by Kendall Johnson

Writing for Light, Part 3

Writing Fire

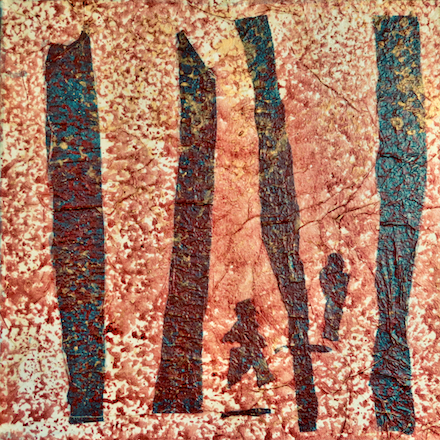

Palmer Canyon 1 (2025) copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson1

The world is burning. Last January the air around my home hung thick with the acrid smoke of the Eaton Fire, some thirty miles west, where thousands of homes were incinerated. Farther west, the Palisades Fire gutted the Pacific Palisades and Malibu, where my cousin Bill grew up and my uncle would surf before going to work in his research job at the RAND Corporation think tank in Santa Monica. Other major fires in California and Oklahoma burned hot in the winter, wet-season month of January, 2025. This reflects fire climate trends internationally.2

It grieves me to watch the incoming evidence of global warming and drought pour in. Lives are being lost, families displaced, towns submerged and burned; yet our collective will to act seems paralyzed. Companies continue fossil-fuel dependency, politicians delay enforcing environmental laws, and voters seem unable or unwilling to stand up and reign them in. Yet my focus is on mega-fires, a longstanding threat growing far more immediate, far worse, highlighted in January 2025 in California and Oklahoma—in winter, no less.3

The Palisades and Eaton fires caused a rethinking of my personal history with fire, a questioning of strategies, and a stirring through ashes to find ways those of us in the creative arts might learn from the heat that fire can bring to our work.

I. Fighting Fire

I know a bit about fire. A thousand years ago, before Vietnam, I’d shed my books, sweaters, and myopia, dropped out of college, and taken up arms in what I’d seen to be the moral equivalent of war. I joined the U.S. Forest Service to fight forest fires. For three years I served on hand crews and fire engines. As I journaled later, I loved it. Those three years as a hotshot were followed by three decades of consulting on fire lines, incident command centers, fire stations, and conferences as a consulting psychologist. In returning to burn areas as a consultant, with the smell of burned brush and timber and the drone of engines and aircraft, I felt at home with the sense of involvement in larger-than-life circumstance.

Stephen J. Pyne, wildland writer and former hotshot, writes about the tragic 2013 Yarnell Hill Fire in Arizona that killed 19 hotshots.4 Subsequent investigations pointed to violations of known safety rules. Pyne goes further, however, calling the incident “literary” in that the deaths can be best understood in terms of human nature itself. When I read Pyne’s cool analysis of the real cause of the 19 Granite Hill Hotshot deaths, I remember myself in a parallel moment and circumstance, caught up in an already lost situation driven by cultural imperatives of toxic masculinity, to prove myself at any cost, in pursuit of my own great white whale.

1964, the famous Coyote Fire burns into Montecito near Santa Barbara. My engine disabled, I’m cutting with the Dalton Hot Shots. It’s my first season as a firefighter. In reconstructed notes later, I write:

The sound of a forest fire rivals that of a jet aircraft. It is a deep moan, a train too close, the collective groaning cry of thousands of plants in an unwilling, transfigurative dance.Surrounded by twisting entrails of flame, where light has become silver and an angelic chorus sings beyond hearing, this is the navel of the world.

5

Palmer Canyon 2 (2025) copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson6

Strategic Contradictions

Irresistibly drawn back by the siren call of emergency years later, as a trauma psychologist I consulted for the U.S. Forest Service, the U.S. Park Service, Cal Fire, and for multiple emergency agencies. Disasters multiplied, and I was fortunate enough to build a practice in on-scene crisis management. I helped emergency management teams handle personnel affected by unanticipated turns of events. In one such event, I began to see cracks forming in my world view.

1988: Third day on the Yellowstone Fire Complex in Montana. This fire was bossed by my old agency, the Forest Service. The smoke hung in the tall trees, and the sound of generators and engines was loud. A hungry hotshot crew runs by me in fire camp, on their way to the chow line. I stop at the concession tent, looking for an “I was there” tee shirt for my son at home. A shirt, emblazoned with a design, grabs my attention. Instead of the basic fire triangle common to most training (fuel, oxygen, and heat = fire), this was rectangular and read:“Fuel + Oxygen + Heat + U.S. Park Service = Fire”

7

This not so subtle jab (approved by the U.S. Forest management team bossing the fire and its concessions) was directed at the U.S. Park Service management team running the fire adjacent to ours, where the less aggressive attack on their fire had led to a runaway firestorm the previous day that had caused our own fire to blow up. Inter-agency conflicts in policy had endangered a town standing in the path of both fires which had now merged. That explained the highway sign that I’d spotted at the town’s outskirts. The name Cooke City had been defaced to read “Cooked City”.

In retrospect, my attitude toward what I saw to be the “laissez faire” approach to fire had its base in my personal need for heroism and my doubts of my own adequacy. Worse, I came to understand that the perspective of “fire as enemy” was promulgated by economic forces. Timber interests and real estate developers had much to gain by furthering the multi-use philosophy of the Forest Service, as it gave them entry to the forest-planning process. The preservationist approach of the Park Service viewed fire differently. Prescribed burns allowed the forest to remain healthy.

Palmer Canyon 3 (2025) copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson8

II. The Way of Fire

It was an “Aha!” moment for me to come to a belated understanding that my fear of prescribed burns was partly an unwillingness to give up my post-adolescent need to prove myself on the firelines, fueled by the toxic male fantasies of domination. The growing knowledge of finding oneself on the wrong side of things is itself a hot spot, especially when the motive for forest management turns out to be detrimental to the forest itself.

The long standing arguments between the Forest and Park Services stem back to their respective inceptions. The Park Service is run by the Department of the Interior, and aims at preserving natural environmental treasures. On the other hand, the Forest Service, run by the Department of Agriculture, views forests and natural resources as crops to be harvested. Fires are primarily used to protect future profit.

The current Administration appears to want to collapse the two into one agency run on the agricultural model. National Forests and Parks would be subject to privatization and sale. Critics foresee the loss of public lands and resources to private interests, domestic and foreign.9

I have to acknowledge that the story takes a significant, perhaps more tragic turn here. For it isn’t just Trump following the orders of the monied architects of Project 202510 that is selling our wildlands,11 but also we ourselves and what we are willing to tolerate in our scramble for personal gain. We have to ask ourselves, Just what is enough?

Indigenous Wildland Management

Embrace fearlessly the burning world

—the title of Barry Lopez’s final book

Rather than view wild land as so many board feet or tons of profit ready for extraction, indigenous peoples have traditionally seen it as their home—a source provider of life and a matrix in which they are participants. Various indigenous groups now internationally provide official input in forest planning.12

The Indigenous concept of “Good Fire” subverts the notion of wild fire as a purely destructive force. While I was laboring under the dictum if it burns, kill it, indigenous peoples worldwide have employed fire more intelligently as a healthy extension of their relationship to the greater world for thousands of years.

I recently had the good fortune to meet Char Miller, a historian of wildland fire suppression.13 In his book Burn Scars, he includes an essay by Bill Tripp on how to stop mega-fires. Tripp, a member of the Karuk people of Northern California, serves as Director of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy for the Karuk Tribe Department of Natural Resources. He is also Co-Chair of the Western Strategy Committee of the International Association of Wildland Fire. Tripp writes:

Fire itself is sacred. It renews life. It shades rivers and cools the water’s temperature. It clears brush and makes for sufficient food for large animals. It changes the molecular structure of traditional food and fiber resources making them nutrient dense and more pliable. Fire does so much more than western science currently understands.14

Both Tripp and Miller applaud the local tribal input to multi-agency fire-management planning. This new development in forest-management practices runs counter to the “aggressive” firefighting dictums issued by the current administration that equate logging with removing fuels. Their end goal is dead set upon removing or neutralizing the obstacles set up by regulatory agencies in the way of privatizing and harvesting forest “crops” by corporations—in short, the colonial approach to resources as profit. The connection is clearly spelled out in Miller’s fire-historical collection documented in Burn Scars.

Palmer Canyon 4 (2025) copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson15

III. Playing With Fire

From burning bushes to eternal flames, from cosmic intermediaries to deity personified, fire is considered a primal and divine force in most cultures worldwide. We gather around hearths in the darkness against the cold. We harness its energy to bend the world to our will. We stand aghast and hide from its fury.

I stand a mile away from the writhing mountain, fire dancing the deaths of billions of biotic beings ranging from low lying bracken up to nearly a thousand 60-foot Coulter pines that had—until this moment—blanketed the mountain on three sides.16

Controlled, fire is our valued friend. Out of control, it will eat us. Fire precedes us, births us, toys with us, and will eventually dissolve us. No wonder so many religious traditions pay homage to its divinity and role in so many origin stories. Many describe spiritual experience as a Holy Fire. To experience forest fire in person is to challenge the adequacy of language.

Now the once-forever fir trees are immersed in coils that snake around the mountain like so many white-hot sun spots. As the trees incinerate by two- and three-hundred-foot tall rolling flames, the pitches and resins inside the trees reach boiling point and blow like artillery shells slamming into mountain sides in war zones far away.17

Apart from learning to adapt to the reality and necessity of wild fire in our mountains and forests, as creators of art, music, drama, and literature, we have much to gain by harnessing the force of fire in our practice.

Writing Fire

As writers, artists, or musicians we struggle to compete with spectacle-driven media patter that becomes the norm after every disaster event. Yet look how the repeated attempts to report on disaster all tend to sound the same. The greatest danger in describing fire in words is to lapse into the sort of newsroom clichés that serve paradoxically to reinforce the reader’s sense of disconnection. Superlatives alone can’t stand up to the reality of experiencing loss, threat, or fear. Or being burned.

While it’s tempting to try to capture the enormity of overwhelming imagery by slathering on cataclysmic adjectives, we do well to remind ourselves of the effectiveness of imagistic poetry. Understatement, implication, concrete imagery, sensory reference, and the use of objective correlatives can set fire to the words and markings we employ. In describing a fire storm at night, I wrote:

Sharp, piercing explosions that thunder off surrounding ridges shake the ground and set off pangs in our long-empty bellies.18

One useful tool to individualize reactions to massive situations is to report what one person sees in such a way that embodies their particular set of values or concerns, interacting with the effects of finding themselves in that situation. I have described the same situation from two perspectives in my account of the 1964 Coyote Fire mentioned previously, where I wrote initially in first person:

“Stay in the trench, don’t run,” came the word down the line. I tried to focus on the ground in front of my face. Small rootlets lay bare, grasses that now never would be. A tiny ant ran in circles, not understanding. I covered it with a handful of dirt. How odd, I thought, that it would likely live longer than me.Later, in third person:

This fire had circled the ridge and was burning up all sides. Time began to slow down. The Captain noticed one firefighter take a moment to bury an ant which was otherwise destined to burn.19

Palmer Canyon 5 (2025) copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson20

Another indirect approach to describing the intensity of a situation might be to highlight the reactions of people through implication. In describing “hot loading”21 of smudge pots while they are burning, I wrote:

The first pot terrified him, but he managed it. The next 10 not so much, and he was keeping up. They smiled white teeth through soot blackened faces. He was part of the crew now, a rowdy hot-loader, a bringer of fire.22

Further, much can be gained through narrow focus and implication in describing a much larger, more complex extended series of events. If done carefully, the image can speak volumes about the people and the times in which the action occurred.

DMZ, 1967 Midnight shelling stops night clouds shield innocent moon birds will not be back. Four hours now remain to sleep hoping this time not to dream. —From “This War Within”23

Also, given the richly diverse cultural treatment of fire, reference to literary or mythic dimensions can add meaning to both writing and art about fire. This can be used as well with related context, and serves to convey historical associations through culturally embedded meaning. Here, I write about my morning of 9/11/01, as I experienced the news first on television from California, and then while working the streets of Manhattan:

how slowly the towering monument to our hubris slides gracefully away a dust column falling in upon itself how smoke and fear and splintered glass transforms upward into lost iridescence spreading far and deep beyond how quickly my familiar protective dissociative cocoon softly buries me in piles of concrete and people dust how somewhere a voice calls to me from within the monstrous chaos what must I now do? —Adapted initially from “Stepping Off O’Brien’s Boat”24

Particularly promising is the manner in which environmental educational programs are becoming part of the curriculum at all levels, both public and private. In young people lies the promise of change, and most K-12 state curricular standards require eco-components at all levels. In Char Miller’s essays, he details field trips in California’s San Gabriel mountains to Big Tujunga Canyon above Sunland, and the San Antonio Dam above Claremont,25 where school-based field trips worked on a forest restoration project and studied the deteriorating flood-control earthen dam and the possibility of disaster when it fails. This is the kind of education that holds hope: in situ, relevant, and realistic.

On the private post-secondary level, the Robert Redford Conservancy for Southern California Sustainability fellowship program of Pitzer College in Claremont incorporates undergraduate, graduate, and faculty fellowships to run the Center and its projects. The Conservancy’s focus is upon environmental analysis and education, and indigenous community partnerships.26

What Can We Do?

If Shiva is having his way with our world, a pyrrhic dance of inevitable endings, if our world is burning up and out as it seems to be, what does it even matter what we do? As writers and artists, musicians and participants of all forms of creative practice, are we like poet Dylan Thomas, merely raging at the dying of the light?27

Or might there be solid reasons to wield our skills despite our limitations? In astronomer Carl Sagan’s Pale Blue Dot, a treatise on how insignificant our tiny planet is against the vastness of space, he urges planetary care and interplanetary exploration. Yet confronting the same depth of darkness vs. our tiny blue dot, particle physicist Brian Cox approaches the issue of significance differently. He asks us to consider the implications of the possibility of our being the only spot of life in the vast universe: what then of meaning? Is all of what we do for nothing?

Cox suggests that even if we are alone in the universe, all the more reason to believe our lives matter, our work has meaning.29 Solitary and transient, all we do on earth could yet be the treasure, the most important part of all that is. Of course it matters what we say and do, and it matters that we do it well, irrespective of outcome.

And it matters to each of us personally, whatever our fate. As two engine captains told me in a debriefing following a burn-over they barely escaped, “We thought we were dead. But finally we decided to go down fighting. Then the wind shifted and we escaped.” Their continuation of the fight beyond all apparent reason, positioned them to act when a brief window opened. Like the two captains, we can persist. And we can best do that creatively using our best skills with courage and open hearts.

steel meets flint sparks darkness to light

Citations and Notes:

Links were confirmed on 4 January 2026.

- Kendall Johnson. Palmer Canyon 1 (2025), mixed media on canvas.

As Johnson notes, the Padua Fire in October 2003 destroyed 60 homes in Claremont, California, and in the nearby gated community of Palmer Canyon, 43 of the 47 homes there were also lost. Fire data are available in The California Fires: Coordination Group A Report to the Secretary of Homeland Security at FEMA (13 February 2004).

Publisher’s Note: Stories about Palmer Canyon include Wildfire Victims Struggle to Rebuild, Two Years Later by Skye Rohde for NPR News (6 January 2006), and Palmer Canyon goes up for sale 12 years after fire by Angela Bailey in the Claremont Courier (30 April 2015). - As Johnson suggests, see reports in the climate-monitoring journal CarbonBrief, especially “Global wildfires burned an area of land larger than India in 2024” (16 October 2025):

https://www.carbonbrief.org/global-wildfires-burned-an-area-of-land-larger-than-india-in-2024/ - See Cal Fire archived incident reports on the January 2025 fires in California:

https://www.fire.ca.gov/incidents/2025 - Stephen J. Pyne. “A Refusal to Mourn the Death, by Fire, of a Crew in Yarnell” in Pacific Standard (12 November 2013):

https://psmag.com/environment/refusal-mourn-death-fire-crew-yarnell-69717/

Publisher’s Note: Pacific Standard, an award-winning nonprofit journal of social justice, reported 20,000 stories during its 13-year history. After its closure, the journal’s archives were acquired in 2020 by Grist, the largest climate-focused newsroom in the U.S., and remain accessible to the public. - Kendall Johnson. “The sound of a forest fire...” was first published in his memoir Chaos & Ash (Pelekinesis, 2020), and the first paragraph of this quotation also appeared in an excerpt from his memoir reprinted at Literary Hub, “On the Ground Fighting a New American Wildfire” (12 August 2020):

https://lithub.com/on-the-ground-fighting-a-new-american-wildfire/ - Johnson. Palmer Canyon 2 (2025), mixed media on canvas.

- Johnson. “1988: Third day on the Yellowstone Fire Complex in Montana...” is from his memoir Chaos & Ash (Pelekinesis, 2020).

- Johnson. Palmer Canyon 3 (2025), mixed media on canvas.

- As Johnson recommends, see this trio of articles:

“Trump escalates war on nature with attack on Public Lands Rule” by Barbara Chillcott at Western Environmental Law Center (10 September 2025):

https://westernlaw.org/trump-escalates-war-on-nature-with-attack-on-public-lands-rule/

The federal proposal to merge wildland fire services as reported by Hunter Bassler in Wildfire Today, “‘US Wildland Fire Service’ unveiled by USDA, DOI on Monday” (15 September 2025):

https://wildfiretoday.com/us-wildland-fire-service-unveiled-by-usda-doi-on-monday/

“The Fight Against Trump’s Pay-to-Play Politics” by Ian Crouch in The New Yorker (27 May 2025):

https://www.newyorker.com/newsletter/the-daily/the-fight-against-trumps-pay-to-play-politics - As Johnson notes, Trump’s appointee to head the Bureau of Land Management is William Perry Pendley, whose Project 2025-based policy is discussed in the article “Land transfer advocate and longtime agency combatant now leads BLM” by Chris D’Angelo in High Country News (8 August 2019):

https://www.hcn.org/articles/climate-desk-bureau-of-land-management-land-transfer-advocate-and-longtime-agency-combatant-now-leads-blm/

The article was reprinted from HuffPost which published it with the title “Backdoor Appointment at Interior Adds to Fears of a Public Land Sell-off: (The new acting director of the Bureau of Land Management appears to be another “fox guarding the henhouse” appointment in the Trump administration.)” - As Johnson suggests, see the discussion by Kate Groetzinger in Western Priorities, “Project 2025 would devastate America’s public lands” (16 July 2024):

https://westernpriorities.org/2024/07/project-2025-would-devastate-americas-public-lands/ - As Johnson recommends, see “How the Indigenous practice of ‘good fire’ can help our forests thrive” by Robyn Schelenz, with video by Jessica Wheelock, at University of California (6 April 2022): https://www.universityofcalifornia.edu/news/how-indigenous-practice-good-fire-can-help-our-forests-thrive

Stanford University reports on a Stanford-led study with the U.S. Forest Service in collaboration with the Yurok and Karuk tribes of Northern California, in “Native approaches to fire management could revitalize communities, Stanford researchers find” (27 August 2019):

https://news.stanford.edu/stories/2019/08/traditional-fire-management-help-revitalize-american-indian-cultures

The National Park Service provides related information in “Indigenous Fire Practices Shape our Land” (updated 18 March 2024):

https://www.nps.gov/subjects/fire/indigenous-fire-practices-shape-our-land.htm

One of the key voices in this movement is Stewart Huntington at ICT (formerly Indian Country Today and now a division of IndiJ Public Media), particularly his article “Ancestor’s Voices: Native leadership brings change to conservation efforts” (8 July 2024):

https://ictnews.org/news/ancestral-voices-native-leadership-brings-change-to-conservation-efforts/ - As Johnson notes, Char Miller is the W. M. Keck Professor of Environmental Analysis and History at Pomona College. He is also a Senior Fellow at the Pinchot Institute for Conservation, a Fellow of the Forest History Society, and a longtime contributor to leadership programs for the Forest Service. I have found two of his books especially helpful:

First, his collection of historical documents in Burn Scars: A Documentary History of Fire Suppression, from Colonial Origins to the Resurgence of Cultural Burning, published by Oregon State University Press in 2024.

And second, his Natural Consequences: Intimate Essays for a Planet in Peril, published in 2022 by Reverberations Press (an imprint of Chin Music Press). - Bill Tripp, as quoted from his article “Our land was taken. But we still hold the knowledge of how to stop mega-fires: The solution to the devastating west coast wildfires is to burn like our Indigenous ancestors have for millennia” in The Guardian US edition (16 September 2020):

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/sep/16/california-wildfires-cultural-burns-indigenous-people

As Johnson notes, when The Guardian ran the article above, the Red Salmon Fire Complex was still burning across Yurok and Karuk tribal lands on which the U.S. Forest Service had prevented prescribed burning and allowed to overgrow.

Publisher’s Notes: Lightning strikes on 27 July 2020 ignited the Red Fire and the Salmon Fire, which eventually merged, and not until 17 November was the resulting mega-fire contained. The Red Salmon Fire Complex burned 144,698 acres across federal lands in the Six Rivers, Shasta-Trinity, and Klamath National Forests in Humboldt, Trinity, and Siskiyou counties of California, including lands where the Hoopa Valley, Yurok, and Karuk Tribes reside.

The Karuk Tribe manages over a million acres of its aboriginal lands along the Klamath and Salmon Rivers. The nearby Slater Fire, another mega-fire which occurred around the same time in 2020 as the Red Salmon Fire Complex, burned 150,000 acres of Karuk ancestral lands, destroying 150 homes and killing two people. Sources:

“Quiet Fire: Indigenous tribes in California and other parts of the U.S. have been rekindling the ancient art of controlled burning” by Page Buono at The Nature Conservancy (2 November 2020):

https://www.nature.org/en-us/magazine/magazine-articles/indigenous-controlled-burns-california/

“California Intertribal Communities Work Together to Provide Emergency Resources During Fires” by Nanette Kelley in Native News Online (30 August 2020):

https://nativenewsonline.net/currents/california-intertribal-communities-work-together-to-provide-emergency-resources-during-fires - Kendall Johnson. Palmer Canyon 4 (2025), mixed media on canvas.

- Johnson. From his unpublished collection of memoir pieces Entering the Grove.

- Johnson. Ibid.

- Johnson. Ibid.

- Johnson. From his memoir piece “The Ridge,” first published in Chaos & Ash (Pelekinesis, 2020).

- Johnson. Palmer Canyon 5 (2025), mixed media on canvas.

- “Hot loading”: Smudge pots used to prevent fruit still on trees from freezing. They typically burned a volatile mix of fuel oil and gasoline, and a truck with a tank of the mix would stop by the burning pot long enough for a worker to pull a hose, open the lid, and thrust a gas-station type nozzle into the flames.

- Kendall Johnson. From his unpublished collection of memoir pieces Entering the Grove.

- Johnson. From “This War Within,” an unpublished memoir piece.

- Johnson. Adapted initially from his unpublished story “Stepping Off O’Brien’s Boat” (2017), then partially incorporated into his memoir Chaos & Ash (Pelekinesis, 2020) and later expanded into Ground Zero: A 9/11 Memoir in Word and Image (Sasse Museum of Art, 2023).

As Johnson notes, I wrote my initial story in response to Tim O’Brien’s story “On Rainy River” (in The Things They Carried, Houghton Mifflin, 1990), about his decision to allow himself to be drafted into the Vietnam War. In 1996, we spoke of our parallel decisions over coffee in Vroman’s Bookstore, Pasadena, where he told me that he always wrote one page at a time, “camera ready,” and never went back for revisions. I was floored. He also said, “We all carry the weight of words and memory.”

See a (very) archived interview in which O’Brien discusses his seventh book, the novel Tomcat in Love: “Caught Up in Conflict” by Michael J. Ybarra in the Los Angeles Times (30 September 1998):

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1998-sep-30-ls-27683-story.html - Char Miller. Natural Consequences: Intimate Essays for a Planet in Peril, pages 115 and 121.

- Robert Redford Conservancy Fellows program:

https://www.pitzer.edu/offices/redfordconservancy/fellows - Dylan Thomas. “Do not go gentle into that good night” at poets.org:

https://poets.org/poem/do-not-go-gentle-good-night - As Johnson notes, Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space (Ballantine Books, 1994) by astronomer Carl Sagan is a riff on the Voyager I photograph of Earth taken on February 14, 1990; in his book, Sagan encourages care of our home planet and exploration of space.

Publisher’s Notes: See images at “What is the Pale Blue Dot?” by NASA/JPL-Caltech (updated in 2020 and 2025):

https://science.nasa.gov/mission/voyager/voyager-1s-pale-blue-dot/

“A Pale Blue Dot” at The Planetary Society includes a 363-word excerpt from Sagan’s book which begins, “Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. ...a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam....” And a 90-second video clip of Sagan speaking on 6 June 1990 about the Voyager Missions:

https://www.planetary.org/worlds/pale-blue-dot - Publisher’s Note: Dr. Brian Cox offers a mind-boggling yet marvelously uplifting message in the video clip “Life Is More Important Than You Think,” from a longer conversation with Joe Scott, “The Island of Meaning With Dr. Brian Cox,” Episode 9 of Answers with Joe on YouTube. The quotation below by Dr. Cox is from 03:11 to 4:13 in the video clip:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h_0otJZKBI8

“The way I look at life is that it’s the most important phenomenon that exists in the universe. Without Life, the universe is, by definition, meaningless. It’s clearly that meaning enters the universe with consciousness, and consciousness is a property of living things. And so, without living things, there’s no meaning. So I think that—let’s flip it round—if this is the only planet in the Milky Way Galaxy that currently hosts an intelligent civilization, then it’s the only island of meaning in a sea of 400 billion stars. And, therefore, we have a tremendous responsibility, notwithstanding our physical insignificance, to protect this island of meaning. If we mess it up, we will be responsible, if that’s the case, for annihilating meaning, perhaps forever, in a galaxy. So I think Life’s important.”

Publisher’s Notes:

- Part 2 of this Writing for Light series by Dr. Kendall Johnson also appears here in Issue 31 of MacQueen’s Quinterly: Finding Hope in Darkness, which includes artworks by Johnson, a sculpture by David Kimball Anderson, and a painting by Dr. Wesley Hurd.

Part 1 of this series is published in Issue 30X (December 2025): Writing in the Dark, which includes five sepia photographs by Johnson. - The seven essays of Johnson’s series Writing for Vision are published in MacQueen’s Quinterly online (Issues 23 thru 27), as well as in a printed collection released by MacQ in August 2025. The book also includes 24 of his visual artworks in full color and an introduction by essayist and poet Kate Flannery, as described in Issue 29 of MacQ:

Writing for Vision: Voicing the New Wild - The six essays of Johnson’s Writing to Heal series appear in MacQueen’s Quinterly online (Issues 16-19, 20X, and 22), as well as in a printed collection released by MacQ in May 2024. The book also includes a few of his poems and 21 of his artworks in full color, as described in Issue 23:

Writing to Heal: Self-Care for Creators

Kendall Johnson

grew up in the lemon groves in Southern California, raised by assorted coyotes and bobcats. A former firefighter with military experience, he served as traumatic stress therapist and crisis consultant—often in the field. A nationally certified teacher, he taught art and writing, served as a gallery director, and still serves on the board of the Sasse Museum of Art, for whom he authored the museum books Fragments: An Archeology of Memory (2017), an attempt to use art and writing to retrieve lost memories of combat; and Dear Vincent: A Psychologist Turned Artist Writes Back to Van Gogh (2020), which is also available in print. He holds national board certification as an art teacher for adolescents to young adults.

Dr. Johnson retired from teaching and clinical work a few years ago to pursue painting, photography, and writing full time. In that capacity he has written a book on art history and seven books of visual art, poetry, and/or essays, including most recently Writing for Vision: Voicing the New Wild (MacQ, August 2025); and Prayers for Morning: Twenty Quartets, a collaboration with poets Kate Flannery and John Brantingham released on Christmas Day, 2024 by MacQ.

MacQ also published Dr. Johnson’s hybrid collection of essays, memoir, poetry, and visual art: Writing to Heal: Self-Care for Creators (May 2024). His memoir collection Chaos & Ash was released from Pelekinesis in 2020, his Black Box Poetics from Bamboo Dart Press in 2021, and his The Stardust Mirage from Cholla Needles Press in 2022.

His Fireflies series is published by Arroyo Seco Press: Fireflies Against Darkness (2021), More Fireflies (2022), The Fireflies Around Us (2023), and Fireflies for These New Dark Ages (30 November 2025).

His shorter work has appeared in Chiron Review, Cultural Weekly, Literary Hub, MacQueen’s Quinterly, Quarks Ediciones Digitales, and Shark Reef; and was translated into Chinese by Poetry Hall: A Chinese and English Bi-Lingual Journal. Johnson serves as a contributing editor for the Journal of Radical Wonder.

More on the Web: By, About, and Beyond

⚡ Dark News (a trio of Fireflies) by Kendall Johnson in Issue 30 of MacQueen’s Quinterly (September 2025)

⚡ Dark News (a second trio of Fireflies) by Johnson in MacQueen’s Quinterly (Issue 30X, December 2025)

⚡ Seeing Beyond the Clamorous Now, an essay and paintings by Johnson in Issue 25 of MacQueen’s Quinterly (September 2024); nominated by MacQ for the Pushcart Prize

⚡ Through a Curatorial Eye: The Apocalypse This Time, an essay and paintings by Johnson in Issue 19 of MacQueen’s Quinterly (August 2023); nominated by MacQ for the Pushcart Prize

⚡ Kendall Johnson’s Black Box Poetics is out today on Bamboo Dart Press, an interview by Dennis Callaci in Shrimper Records blog (10 June 2021)

⚡ Self Portraits: A Review of Kendall Johnson’s Dear Vincent, by Trevor Losh-Johnson in The Ekphrastic Review (6 March 2020)

⚡ On the Ground Fighting a New American Wildfire at Literary Hub (12 August 2020), a selection from Kendall Johnson’s memoir collection Chaos & Ash (Pelekinesis, 2020)

⚡ A review of Chaos & Ash by John Brantingham in Tears in the Fence (2 January 2021)

| Copyright © 2019-2026 by MacQueen’s Quinterly and by those whose works appear here. | |

| Logo and website designed and built by Clare MacQueen; copyrighted © 2019-2026. | |

|

Data collection, storage, assimilation, or interpretation of this publication, in whole or in part, for the purpose of AI training are expressly forbidden, no exceptions. |

At MacQ, we take your privacy seriously. We do not collect, sell, rent, or exchange your name and email address, or any other information about you, to third parties for marketing purposes. When you contact us, we will use your name and email address only in order to respond to your questions, comments, etc.