|

|

|

|

|

| Issue 31: | Jan. 2026 |

| Essay: | 2,656 words |

| + Footnotes: | 444 words |

Essay and Visual Artworks

by Kendall Johnson

Writing for Light, Part 2

Finding Hope in Darkness:

Looking, Acting, and Telling

Reaching (2016) copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson1

Gentle goddess Persephone brings Spring, though her backstory is considerably less sweet, more telling. Violated, abducted from Light’s garden that she loved, forced to remain in darkness far below. Yet she overcame despair; made of sterner stuff she discovered her own light while tending others, newly arrived in the darkness.

When their lives were taken and they found themselves wandering lost in the underworld, Persephone appeared. She guided them, helping the lost to find ways to adapt to their new life in the dark. She would return to the surface world only once annually, to herald the Spring. She brought beauty to the world.

Beauty in a World of Fear

Just what constitutes beauty is an open question, as is the way it can be best conveyed. Beauty is often imagined by non-artists as the principal purpose of art, although that is itself open to question. At the height of the modernist era in the 19th century into the 20th, the pursuit of art for art’s sake seemed an important focus. Indeed, mid-century modernists especially in New York following WWII seem to have freed themselves from the worlds of war and depression and launched headlong into a world of abstraction.

Art theorists in midcentury, however, began to question the presumptions of the modernist artists. Concerned with questions such as whether “high,” or sophisticated art can be distinguished from popular art, universal from subjective and relative truths, or whether the purpose of art should be to experiment with approaches or examine and critique social forms, they closely examined the purpose of art and the role of beauty.

In an Early 1960s High School Art Class

Steeped in these questions from her courses in pursuit of a Master’s degree in Fine Arts at Scripps College nearby, artist Gerry Turner introduced a diverse group of senior high school students to the world of art, in a beginning art class at Claremont High School.2 I was in that class. On the first day we sat around broad tables, expecting Ms. Turner to hand out pencils, pens, paints and paper, and to turn us loose. Instead, she sat calmly in the center of the room and asked us:

“What do you think Art is?” She gave us time to think about that. Then: “And what is beauty?” She waited, patiently, for us to begin to talk.

I have been seeking answers to those and similar questions ever since. Two others in that class also pursued art. David Kimball Anderson went on to become an acclaimed sculptor. Dr. Wesley Hurd became a theologian and founded an art institute where he guides students in examining spiritual questions, art, and contemporary culture. We came together again decades later in an impromptu exhibition of our artwork at our fifty-year high-school class reunion. I found that all of us, in our own ways, were still grappling with Ms. Turner’s questions.

Bakersfield Spur (2022) copyrighted © by David Kimball Anderson3

David Kimball Anderson: Looking Closely

Recently, driving from L.A. up through the central valley toward Bakersfield, I pondered these questions, and thought about my relationship with David that had now renewed after more than sixty years. He had known that I was floundering in high school, and had introduced me to Jack Knapp, the cross-country coach. Jack pulled me in, believed in me, and sent me running a far longer race than I could have imagined at the time. Jack and David had given me direction and had saved my life.

The remaining oil pumps, feed lots, and ranches I passed on that long drive bespoke the hardscrabble history of the Bakersfield area, as did the retrospective exhibition of David’s artworks: life-sized welded steel sculptures of machinery, water cisterns, rusted iron-works, tools, and faded signs. Objects from the fields, roadside stands, and abandoned lots stood in two large exhibit rooms at the Bakersfield Museum of Art—a tribute to the passage of time. It was about the process of being.

In his presentation at the opening of the exhibition, David told us how he would travel the back roads looking for interesting things, photographing them in situ. Back in his Santa Cruz studio, the photographs would guide his fabrication, cutting and joining steel he had purchased at a metal supplier in Bakersfield. His journeys in search of promising parts, objects of contemplation, were often assisted by another artist friend, noted ceramist Stan Welsh, who himself had been guided by David’s art teacher in Claremont, Gerry Turner.

More than a tribute to a place, the exhibition was an invitation to see.

Look to See

In contemporary thinking, much is made of the term “gaze.” Never neutral, the gaze is more than just staring. It is shaped by feelings, attitudes, social power and position, values, and aesthetics. How and where we look determine what we see.

Reporting for an online Buddhist journal her interview with David, teacher and artist Sarah C. Beasley—herself a practicing Buddhist—writes, “For him, spiritual practice includes not just meditation and mindfulness ... [but also] active observation and thus participation.” Beasley relates how conversations with David point to more: “Taken as an invitation—to observe one’s mind, the outer world, and the spaces between—all inform his work as an observer, artist, and good human.”4

At the Bakersfield exhibition, David spoke to us of working with plates of steel, about how steel first appears appears solid, but releases steam when heated by cutting torch. “It’s porous,” he pointed out, “has water trapped inside it by the process of refining iron ore.” I remember the great blast furnaces at the Kaiser Steel plant in Fontana, to the east of Claremont, and how the intense fires would light the night sky. David finds critical to his process of working with steel, that leaving the patina of rust on found pieces, and leaving rust to develop on new ones, result in an aesthetic delight. In the exhibition catalog essay by Maria Porges, David is quoted as saying:

Steel is nothing more than dirt in a more sophisticated arrangement, and steel wants nothing more than to go back to being dirt.5

Some 60 years after we met in high school, with huge distances travelled in between, I found myself enchanted with David’s evolved work, and with the process of looking at it in order to see beyond. The purpose of beauty in his artwork, the purpose of his art itself, is to help us to learn to see our world.

Meet Me in the Silence (2016) copyrighted © by Wesley Hurd6

Wesley Hurd: Healing Community

Painter, art lecturer, college professor, and theologian Wesley (Wes) Hurd operates at multiple levels. His overriding concern in each of these realms is spiritual. In the capacity of art teacher, Wes Hurd interacts with young people who are growing up in a society wracked by too much change, too soon. He works with local art organizations that attempt to interject the aesthetic perception of human experience of that change into the daily life in their community. Hurd sees art as the key to experiencing the interior life of human experience, as it is affected by the exigencies of living in a world driven by material concerns. Art can give voice to, and teach, our deeper selves. His artwork is in service of this goal, not just for individuals, but for whole communities in which we live.

Following a career of university work as a professor of Theology and Art, Hurd retired into tutoring and abstract painting. Following several difficult personal losses in 2014 and 2015, he endeavored to give artistic voice to his suffering in a bid to “paint himself” through his dark time of the soul—a series on loss. He set up nine large canvases and began his inward journey. Midway through this process, on October 1, 2015, he was interrupted by news of a mass shooting at the nearby Umpqua Community College. He managed to incorporate his reaction to this news of our violent, tragic nature, into the remaining paintings of his loss series.

A quotation by Hurd specific to this series:

These paintings continue my practice of finding abstract forms that evoke and investigate the central subject matter of my art—human interiority and the human condition in the world as I see and experience it.7

I later wrote to him:

There is a deep part of us that relates to those who would transgress. We all know that, pushed far enough, there is little we are not capable of. Maybe that’s why the bleeding of the world affects us so deeply. But sometimes the world’s pain falls on fertile soil. When we are reeling with personal hurt, the pain of others gains power. Most of us shrink deeper inside, closing our eyes and hearts. Some, however, use the hurt for the sake of others. Another famous theologian once said that it isn’t despite our own pain, or because of it; rather it is through our own pain that we find what it takes to help others.

When Wes Hurd showed his work to his friend Eliot Grasso, acclaimed composer, musician, and founder of the Gaelic ensemble Drèos, Grasso asked if he could compose a score based upon the series. His intent was not to interpret the visual experience of the paintings, but to “guide the listener through the emotional space” created by response to the paintings. Taken together, with the paintings standing behind the ensemble, and the comments of Hurd and Grasso orienting the audience to the process of their collaboration beforehand, the community became a part of the shared lament.

Because of our past association, my wife, Susie Ilsley (who grew up on Wes Hurd’s street in Claremont), and I (because of my past trauma work following the Thurston High School shooting in Springfield, Oregon in 1998) were invited to attend the premier exhibition of Hurd’s and Grasso’s The Odyssey of These Days.

I wrote to Wes:

Walking into the auditorium where the premier of Odyssey of These Days opened to your community audience, I was struck by the fact that it was indeed a community. These were your people, the people affected by the mass shooting. They were friendly, spoke in small groups, but in hushed tones. Something was happening here that was real, a part of their lives. Susie and I took our seats, aware that everyone grew quiet, expectantly, hopefully.

Keening pipes and fiddles, cello, bass and drums, cried through the paintings, stepping past denial, embracing anxiety, rage, and anguish, overseen by the somber grays of the paintings.8 At the conclusion of the concert and viewing, the audience—members of the community torn by the violence in their town, which was violence seen across the land, and the world—were able to meet and embrace and talk to each other, to share their personal stories, and be heard by others.

Another quotation from Wes:

Visible form is to visual art what sound is to music. Where sound has the power to reveal and loosen unthought, unfelt sensibilities to the individual soul, visible forms perform similarly. Especially for those who find themselves fascinated by the peculiar voice and language of lyrical abstract form.9

I wrote later to him:

Thanks for including us in this important moment. While we do not live close by, we have a sense of the community. I worked several summers in my youth on a farm not far from the campus where the shooting occurred. More than that, as a trauma shrink, I worked in the aftermath of the violence at Thurston High, Columbine High, Parker Middle, Buell Elementary, Santee High, Granite Hills High, etc., etc. I know what it does. And I know it takes more than “our prayers go out for you” to deal with that kind of pain. Your outreach was direct and cut through the community’s sense of isolation. Moreover, the interaction among those following the performance was clearly healing.

Wanting More (2017) copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson10

The Purposes of Art and Beauty

First recorded the year that David, Wesley, and I took Gerry Turner’s art class, the same year we graduated from high school, Bob Dylan’s timeless anthem “Blowin’ in the Wind” heralded a decade of radical change which would affect the three of us in different ways. The times, as he foretold the next year, were a-changin’.11 The revolution against racial discrimination, the wide-spread protests against the Vietnam war, civic unrest, and the reactive culture wars that followed, swept us up and onto diverse paths.

My own walk through the intervening years has involved wrestling with those concepts within a different context. Like David’s, my journey took me to the war zone of Vietnam, through coastal firefights north of the DMZ, and the self-questioning of many of us above and below decks. Further, my subsequent choice to leave the safety of teaching and become an on-scene trauma consultant in emergency work and school shootings, recalled and brought back my own distressing moments as well as some of my best work. Yet, again, it was painting, photography, creative writing, and especially the process of talking with visitors to my exhibitions that helped me heal my own wounds.12

The postmodern art theories developed over the time since David, Wes, and I sat in class together, questioned concepts such as a single, objective reality, a universal truth and reason, a fixed human nature, and external linguistic referents, suggesting that all are relative to the particular communities and groups that share them. Further, according to the postmodernists, all inclusive “grand stories” of social or historical development serve only to oppress and marginalize those who do not share them. The use of media, appropriation, juxtaposition, everyday and found objects, and irony challenged those modernist grand assumptions, particularly the idea that claims that beauty and truth can be valid for all groups, cultures, or traditions.

I like to think that the three of us found our way through the tangle of the current diversity of approaches to art, now sometimes termed post-postmodern or meta-modernism which both acknowledges the postmodern critique of art for art sake, and expands the aesthetic conversation regarding beauty and purpose. Equally important, I think this opens the way to rethink the darkness that seems to hang over all of us through this time of the existential threats of climate change, political fracture, and social shift. How we see our world is in part determined by how we look, and how we respond.

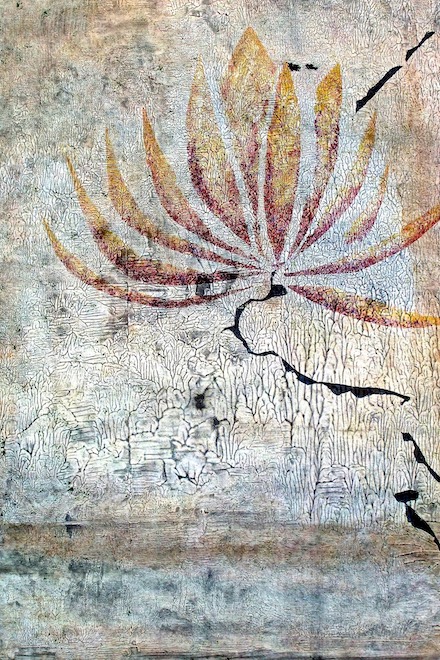

Lotus Dreaming (2018) copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson13

Working Through Darkness

We don’t need perfect lighting to make artwork, whether we are painters, sculptors, or writers. In fact, as many creators know, sometimes adversity gives us an abundance of both material and inspiration. Darkness, particularly when we raise our sights above immediate uncertainty and fear, highlights much of our lives that is of critical importance. And what results, on our canvases, prints, sculptures, and written pages, through our spoken words and our silent actions, is often of the most help to our audience. And to us.

As creative people, we must constantly remind ourselves to look up. We are not defined by our bank accounts and possessions. Our prestige vis-à-vis others in our fields, our job titles, or whether we made the pages of the most recent Who’s Who cannot comfort us if we focus on how things all fall away. While seasons change and entropy rules, we can see what is before us in the world closely, through David’s eyes for example, and appreciate the depth and delight of all that still is. We can respond to what we see mindfully and look to what others around us need. To those in pain who fear they suffer alone, writers and artists can clearly voice the empathy and support of the broader human community.

Citations and Notes:

Links were confirmed on 30 December 2025.

- Kendall Johnson. Reaching (2016), acrylic on canvas; appears with the title Branching II in Johnson’s Pasture: Living Place, Living Time (Claremont Heritage, 2018; page 40), and at the California Botanic Garden in 2018.

- Publisher’s Note: Geraldine (Gerry) Turner (1930–2006) was a significant figure in the California ceramics and art-education communities. Born in Iowa, she graduated from Iowa State Teachers College in 1952; taught junior high in Pueblo, Colorado; and studied under the renown ceramics artist Paul Soldner at Scripps College in Claremont, California, where she received an MFA degree in Ceramics. Through the 1960s, Gerry also taught art at Claremont High School, serving several years as chairman of the art department. Source: “Geraldine Turner” obituary:

https://www.steinhaushollyfuneralhome.com/obituaries/geraldine-turner - David Kimball Anderson. Bakersfield Spur (2022), sculpture (steel, wood, and neon; 34x106x45 inches); in the exhibit Bakersfield Standards at Bakersfield Museum of Art, 25 September through 3 January 2026:

https://www.bmoa.org/exhibits/david-kimball-anderson-bakersfield-standards - Sarah C. Beasley, quoted from “The Art and Nature of Meditation with David Kimball Anderson” published in Buddhistdoor Global (10 July 2018):

https://www.buddhistdoor.net/features/the-art-and-nature-of-meditation-with-david-kimball-anderson/ - David Kimball Anderson, quoted in Bakersfield Standards Exhibit Catalog by Maria Porges (Bakersfield Museum of Art, 2025).

- Wesley Hurd. Meet Me in the Silence (2016, acrylic on canvas, 51x47 inches) from the nine-painting series The Odyssey of These Days:

https://www.odysseyofthesedays.com/paintings - Wesley Hurd, “These paintings continue my practice...” is from “Intent” (paragraph 7), the combined artist statement by Wes Hurd and Eliot Grasso for The Odyssey of These Days (2017):

https://www.odysseyofthesedays.com/intent#intent1 - A digital album of Eliot Grasso’s original Breton music composed to accompany The Odyssey of These Days is available at:

https://eliotgrasso.bandcamp.com/album/odyssey-of-these-days - Wesley Hurd, “Visible form is to visual art...” is from his Statement at his website:

http://www.weshurd.com/statement - Kendall Johnson. Wanting More (2017), acrylic on canvas (40x30 inches). Detail from this painting originally appeared in Midcentury Reconsidered (Cholla Needles Press, 2018).

- Bob Dylan’s song “The Times They Are a-Changin’” is the title track from his 1964 album of the same name.

Publisher’s Note: Dylan’s earlier song “Blowin’ in the Wind” Still Asks The Hard Questions as reported by Brian Naylor for NPR News (21 October 2000), unfortunately as timely today as it was then. - As Johnson suggests: See my Fragments: An Archeology of Memory (Sasse Museum of Art, 2017) and Ground Zero: A 9/11 Memoir in Word and Image (Sasse Museum of Art, 2023).

- Kendall Johnson. Lotus Dreaming (2018), composite photograph of two acrylic on canvas paintings (each one, 40x30 inches).

Publisher’s Notes:

- Part 3 of this Writing for Light series by Dr. Kendall Johnson also appears here in Issue 31 of MacQueen’s Quinterly: Writing Fire, which includes five paintings by Johnson.

Part 1 of this series is published in Issue 30X (December 2025): Writing in the Dark, which includes five sepia photographs by Johnson. - The seven essays of Johnson’s series Writing for Vision are published in MacQueen’s Quinterly online (Issues 23 thru 27), as well as in a printed collection released by MacQ in August 2025. The book also includes 24 of his visual artworks in full color and an introduction by essayist and poet Kate Flannery, as described in Issue 29 of MacQ:

Writing for Vision: Voicing the New Wild - The six essays of Johnson’s Writing to Heal series appear in MacQueen’s Quinterly online (Issues 16-19, 20X, and 22), as well as in a printed collection released by MacQ in May 2024. The book also includes a few of his poems and 21 of his artworks in full color, as described in Issue 23:

Writing to Heal: Self-Care for Creators

David Kimball Anderson

was born in Los Angeles, studied art and metallurgy at Claremont Graduate School, and attended the San Francisco Art Institute in the late Sixties. He has been a practicing studio artist since 1969. Beginning in 1970, he worked for two years as an assistant to the American ceramicist Peter Voulkos, who had begun to make monumental bronze pieces. For his own work, Anderson manipulates a range of materials—steel, fiberglass, bronze, aluminum, and wood. His résumé includes exhibitions at Bakersfield Museum of Art, Monterey Museum of Art, Museum of Fine Arts in Santa Fe, San Francisco MoMA, Sheldon Museum of Art in Nebraska, and SOFA Chicago, among numerous others. He has received three Arts Fellowships from the NEA, and lives and works in Santa Cruz and the Bay Area.

To learn more, see Anderson’s Work and Still Life galleries at his website, as well as A brief personal history.

Wesley Hurd

is a free-lance lecturer and mentor specializing in modern and contemporary visual art. Born in Claremont, California, he studied fine art and art education at Southern Oregon College, graduating in 1967. He and his wife, Carol, have lived in Eugene, Oregon, since 1977. In 1989, he began his studio practice. Dr. Hurd holds a graduate degree in theology, a PhD in education, and an MFA in Painting from the University of Oregon. In 2007, he was nominated for the Portland Art Museum’s Northwest Contemporary Art Award. He co-founded BlueTower Arts Foundation, a nonprofit focused on education, mentoring, and fostering contemporary art, where he serves as a principle teacher and chairman of the Board of Directors.

To learn more, see the artist’s website, https://www.weshurd.com/work, which features four dozen of his paintings, including his series The Odyssey of These Days.

Kendall Johnson

grew up in the lemon groves in Southern California, raised by assorted coyotes and bobcats. A former firefighter with military experience, he served as traumatic stress therapist and crisis consultant—often in the field. A nationally certified teacher, he taught art and writing, served as a gallery director, and still serves on the board of the Sasse Museum of Art, for whom he authored the museum books Fragments: An Archeology of Memory (2017), an attempt to use art and writing to retrieve lost memories of combat; and Dear Vincent: A Psychologist Turned Artist Writes Back to Van Gogh (2020), which is also available in print. He holds national board certification as an art teacher for adolescents to young adults.

Dr. Johnson retired from teaching and clinical work a few years ago to pursue painting, photography, and writing full time. In that capacity he has written a book on art history and seven books of visual art, poetry, and/or essays, including most recently Writing for Vision: Voicing the New Wild (MacQ, August 2025); and Prayers for Morning: Twenty Quartets, a collaboration with poets Kate Flannery and John Brantingham released on Christmas Day, 2024 by MacQ.

MacQ also published Dr. Johnson’s hybrid collection of essays, memoir, poetry, and visual art: Writing to Heal: Self-Care for Creators (May 2024). His memoir collection Chaos & Ash was released from Pelekinesis in 2020, his Black Box Poetics from Bamboo Dart Press in 2021, and his The Stardust Mirage from Cholla Needles Press in 2022.

His Fireflies series is published by Arroyo Seco Press: Fireflies Against Darkness (2021), More Fireflies (2022), The Fireflies Around Us (2023), and Fireflies for These New Dark Ages (30 November 2025).

His shorter work has appeared in Chiron Review, Cultural Weekly, Literary Hub, MacQueen’s Quinterly, Quarks Ediciones Digitales, and Shark Reef; and was translated into Chinese by Poetry Hall: A Chinese and English Bi-Lingual Journal. Johnson serves as a contributing editor for the Journal of Radical Wonder.

More on the Web: By, About, and Beyond

⚡ Dark News (a trio of Fireflies) by Kendall Johnson in Issue 30 of MacQueen’s Quinterly (September 2025)

⚡ Dark News (a second trio of Fireflies) by Johnson in MacQueen’s Quinterly (Issue 30X, December 2025)

⚡ Seeing Beyond the Clamorous Now, an essay and paintings by Johnson in Issue 25 of MacQueen’s Quinterly (September 2024); nominated by MacQ for the Pushcart Prize

⚡ Through a Curatorial Eye: The Apocalypse This Time, an essay and paintings by Johnson in Issue 19 of MacQueen’s Quinterly (August 2023); nominated by MacQ for the Pushcart Prize

⚡ Kendall Johnson’s Black Box Poetics is out today on Bamboo Dart Press, an interview by Dennis Callaci in Shrimper Records blog (10 June 2021)

⚡ Self Portraits: A Review of Kendall Johnson’s Dear Vincent, by Trevor Losh-Johnson in The Ekphrastic Review (6 March 2020)

⚡ On the Ground Fighting a New American Wildfire at Literary Hub (12 August 2020), a selection from Kendall Johnson’s memoir collection Chaos & Ash (Pelekinesis, 2020)

⚡ A review of Chaos & Ash by John Brantingham in Tears in the Fence (2 January 2021)

| Copyright © 2019-2026 by MacQueen’s Quinterly and by those whose works appear here. | |

| Logo and website designed and built by Clare MacQueen; copyrighted © 2019-2026. | |

|

Data collection, storage, assimilation, or interpretation of this publication, in whole or in part, for the purpose of AI training are expressly forbidden, no exceptions. |

At MacQ, we take your privacy seriously. We do not collect, sell, rent, or exchange your name and email address, or any other information about you, to third parties for marketing purposes. When you contact us, we will use your name and email address only in order to respond to your questions, comments, etc.