|

||

|

|

|

| Issue 17: | 29 Jan. 2023 |

| Essay: | 2,962 words |

| Footnotes: | 52 words |

By Kendall Johnson

From a series on self-care for writers

Writing to Heal, Part 2: Diving Deep

Whether we write fiction, nonfiction, or poetry, we often draw upon personal experience to inform our writing. Yet some things are hard to write. Not just because they are conceptually challenging or hard to put to words, but because they light off some unbearable interior fireworks. How do you forge ahead and write when the sounds and smells and wild imaginings that your writing has triggered in you prevent you from doing so?

In my own writing about difficult things, I’ve drawn upon lessons I learned and taught while consulting among emergency crisis teams nationally and internationally, in fire camps, field commands, and disasters from Columbine to Lower Manhattan. I am hopeful that they will help you write your way through your difficult material to uncover gems of experience. By practicing what I preached to others, I manage to find ways to keep functioning—including writing.

This discussion looks at why such reactions occur, and ways to understand them to guide self-care. In part I hope to provide insight into how to avoid further hurt. Equally important, I hope to give suggestions about what I’ve done to deal with my memories, flashbacks, hauntings, and dreams in order to move ahead. This isn’t about therapy, it’s about going ahead with the work.

How Memories Haunt

Extreme situations and traumas encode themselves in memory differently than “normal” activities do. Like split-second scenes caught by strobe lights, some memories lay down more vividly and permanently. With those memories are the accompanying survival-focused emotions. Trauma specialists call these “flash-bulb,” or “hot” memories. Some are conscious but many lie beneath consciousness, and most are fragmentary. When activated by reminders, they often return unbidden to haunt us, and when they do they tend to elicit the same internal endocrine response they did when initially formed. If you reacted one way in an emergency, then you are likely to react in the same way if you are suddenly reminded of the incident.

A reminder of a sudden car accident (seeing or hearing a crash, watching one in a movie, or even reading about a bad smash-up) may trigger a flood of the same internal chemicals that had taken place however long ago. Writing scenes of building intimacy, for example, may suddenly trigger flashes of earlier personal abuse. Result: the brain’s upset disrupts writing. The mind interprets the upset as immediate threat.

While writing a short memoir piece about a burn-over on a big fire (for the story “Flashback” in Black Box Poetics1), I have trouble catching my breath:

Suddenly I can’t breathe. I am hit by the all-too-familiar panic of oxygen deprivation and I can’t breathe deeply enough. The acrid smoke smells of eucalyptus and sage, and the room has turned dark. My skin burns through the army blanket I’ve wrapped over my face, and small glowing holes begin to appear. People near me are yelling.

I work at controlling my breath, breathing slowly in for four seconds and then holding it in for another four. Then I breathe out slowly for four seconds and hold it out for four more. Gradually the panic subsides and I can proceed with writing the incident.

Perceived threat can be sensed in the external world (perceptions of real threats themselves, reminders, or similar situations that previously proved dangerous), or can be in reaction to internal cues (memories, flashbacks, nightmares, or unconscious associations). Emergency responses are the mind/body’s reaction to threat. Seven basic response types can take place in several degrees of intensity. Further, the response types may result in disengagement, or in engagement with the perceived source of threat. Understanding the underlying physiology of emergency reactions gives clues on how to manage them.

The following discussion may be a bit technical, but bear with me: it is important to understand how this works.

The Biochemistry of Survival

Normal brain function is the result of a balanced interaction of a myriad of natural neurochemicals. When emergency strikes, and direct threat is perceived, normal brain chemistry is altered. This in turn causes changes in brain function, in feeling and mood, and in physical capability. Simplified, three key hormones are released in a balanced cascade: excitors (to stimulate reactions), moderators (to stay balanced and functional), and suppressors (to blunt pain and fear, and increase sense of well-being). This powerful jolt mobilizes the mind and body to survive the threat.

While writing a short memoir piece about the chemistry of emergencies (for the story “Grandma and the Bug” in Chaos & Ash2), I have trouble with sudden feelings of pain in my hands, and flooding with a dozen visual images of similar stories:

When the jack collapsed the VW on her grandson, eighty-year-old, 113-pound Dorthea grabbed the bumper and lifted the front end off of him. In doing so she ruptured two discs, sprained her right shoulder, and tore several muscles. And saved his life. Later the emergency physician explained that she’d been flooded by catecholamines that had fueled her body and endogenous opioids that had dulled the pain at the time, dissociated her awareness of emotions so she could function, and gave her the sense of being able to manage. She didn’t panic, and did what she needed to do. The fear and pain all came later.

I stand up, shake my hands, and go make a cup of coffee. I check email, and then sit back down and proceed with writing the memoir.

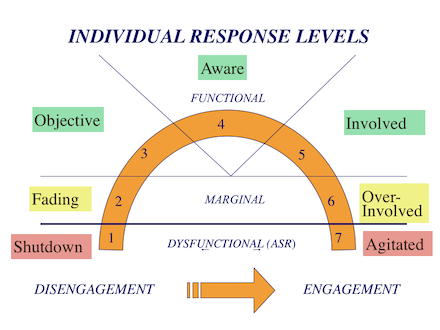

Things that go wrong in our responses to threat are generally a result of too much of one, or too little of another of the emergency hormones. Response patterns range from fully functional to dysfunctional as follows:

- Functional responses can range between “Objective,” “Fully Present,” and “Taking Action,” depending upon the situation, the result of a balanced cascade of emergency hormones.

- Marginal responses are less than fully functional, and are either “Fading” (difficulty thinking clearly or making decisions, low emotional involvement, and physical inertia) or “Overreactive” (racing thoughts and imagination; nervousness; intense feelings of anger, sadness, or fear; and difficulty sitting still or even directing actions effectively).

- Dysfunctional responses can take the form of “Shutdown” (sluggishness or paralysis, confusion, unconcern, inability to act, even physical shock symptoms) or “Agitation” (random, ineffective movement, shaking, panic, rage, incapacitating grief, inability to plan).

What Balance or Imbalance Feels Like

The internal experience of each level of reaction is important for writers to identify, as writers often work in isolation. They don’t always have the benefit of someone observing them, and need to be able to identify their reactions in order to manage them. This includes their own observation of what they themselves feel, and what their world looks like to them.

| Level: | Feels Like: | World Looks Like: |

| 1. Shutdown | No feeling | Random, surreal, chaotic |

| 2. Fading | Things don’t seem important | Out of control, disconnected |

| 3. Objective | Calm | Consequential, but understandable |

|

4. Fully Present (Aware) | Wide range, moderate feeling | Understandable, possibilities |

|

5. Taking Action (Involved) | Focused: anger, fear, sadness | Compelling |

|

6. Overreactive (Over-Involved) | Overwhelming feeling | Compelling, but out of control |

| 7. Agitation | Unbearable feeling | Unendurable |

These seven patterns together form a continuum ranging from under-responsive to over-responsive. The middle three reaction patterns (Numbers 3-5) in the table above are the most adaptive. Another way to visualize them is the following diagram:

Copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson. All rights reserved.3

Managing Agitated or Over-Reactions

Revisiting difficult circumstances, whether in the face of reminders, recurrent imagery like dreams or flashes, or as a result of digging deep into memory, can result in marginal or even agitated reactions. Here are signs to look for to identify troubling over-reactions, and steps to take to manage them.

If you are experiencing the following, you are likely becoming over-involved or agitated:

- breathing rapidly

- having feelings you can’t explain

- watching others acting in slow motion, or not responding quickly enough

- noticing that time seems to be going too slowly

- hearing others say things that imply you are over-reacting, such as: “Hey, slow down!” or “Get a grip!” or “What’s the matter?”

- seeing others as not acting in a way that fits the seriousness of the situation

- seeing the situation as overwhelming

- panicking, raging, or having overwhelming emotion

While writing a short memoir piece about a Vietnam firing mission north of the DMZ (for the story “Home Improvements” in Chaos & Ash2), I have trouble with intense feelings of nightmarish claustrophobia:

Cold C-rats for two weeks seasoned lightly with aluminum oxide paint chips from the overhead, loosened by the mind-numbing concussions every night. Beans and motherfuckers and everything looked and tasted the same on the dim red lights, smelling of oil and cordite. Trying not to scream from claustrophobia in the pulsing darkness. We brought evil with us and congealed it there.

Realizing I’m stuck in memories of the pounding concussions and acrid smells, I stand, practice the four-count breathing exercise, and then take a quiet walk around the block. I feel the bite of the cold, and smell the plants. I crush different types of leaves and notice the different scents. An hour later I can go back and start writing the incident.

I have found that in order to slow and balance my own response and moderate my reactions, I try several different steps:

| Tools: | Steps: | |

| Breath → | Slow your breathing: breathe in for a four-count, hold for four, breathe out for a four-count, hold for four. Repeat for a total of four cycles. | |

| Activity → | Do some stretching; take a walk or a gentle run, but don’t over-do. | |

| Direction → | Find a useful task to accomplish; find support and assistance. | |

| Relaxation → | Change your setting; sit down, look around you, and notice details. | |

| Focus → | Ignore memories and imagination: focus on what is going on around you in the here and now. | |

| Self/other-talk → | Use soothing and calming self-talk; repeat saying things to yourself that are supportive and calm. Speak with others about what is going on. | |

|

Imagery/ expectations → |

Visualize yourself in a place that you have found safe in the past; write about it. Imagine yourself taking deliberate actions with positive outcomes. | |

Managing Fading or Under-Reactions

Writing projects that, for whatever reason, directly explore personally difficult moments, may also trigger marginal fading or even shut-down reactions. Again, here are signs to look for to identify troubling under-responsiveness, and steps to take to manage it.

If you are experiencing the following, you may be fading out or shutting down:

- watching others behaving in ways that seem unnecessary

- feeling little or no emotion

- not noticing your body

- hearing others say things that imply you are under-reacting, such as: “Are you okay?” or “Hey, listen to me!” or “Come on, pay attention!”

- seeing others moving too quickly, or even jerkily

- noticing that time seems to be passing too quickly or in spurts

- not being able to make sense of things

- seeing the situation as unimportant or irrelevant

I have found that in order to energize my own response and moderate my reactions, I try these steps:

| Tools: | Steps: | |

| Breath → | Increase your breathing: take quick, panting breaths for several seconds. Two or three sets of ten panting breaths will oxygenate your system, but don’t overdo. | |

| Activity → | Get up and move; shake it off. | |

| Direction → | Find some task to accomplish; find support and assistance. | |

| Engagement → | Block memories and imagination: focus on the present. Change your setting to one that requires you to engage with others. | |

| Focus → | Pay attention to whatever is going on around you in the here and now. | |

| Self/other-talk → | Repeat saying things to yourself that are supportive and encouraging. Remind yourself how you have coped with hardship in the past. Speak with others about what is going on. | |

|

Imagery/ expectations → |

Visualize yourself in a place that you have found safe in the past. Imagine yourself taking deliberate actions with positive outcomes. | |

Warning Signs

If you notice either of these sets of reactions (Agitated or Fading) to reminders, thoughts, flashbacks or nightmares, and you are unable to rebalance yourself through the above self-management, your reaction is more than normal. Beyond this point, you should not wander. Specifically, get help from family, friends, professionals, or call 9-1-1 if you:

- find yourself so disoriented that you don’t remember your own name, the date and time, or if you can’t recall what’s happened over the last day.

- find yourself preoccupied, perseverating, or ruminating uncontrollably.

- find that brief flashbacks have become unmanageable hallucinations.

- can’t make yourself stay in the present.

- are raging, inconsolable, or terrified.

- find yourself performing rituals repeatedly.

- are contemplating taking violent action against others or yourself.

It may help to assume that your reactions, however unexplainable, disproportionate, or random they may seem, may point to blocked or hidden memories that are held by your body, if not in your conscious memory. Professionals—particularly those practicing body-based therapies like eye-movement desensitization (EMDR), deep tissue massage, movement therapies, Neurofeedback, and/or art-based therapies—may help with exploring and understanding less-surface layers of experience.

While writing a short memoir piece involving PTSD nightmares (for the story “Home Improvements” in Chaos & Ash2), I vividly recall a nightmare from the first year or so of returning home:

Rolling off the bunk, he would dive for his boots. Can’t find them, and he would go down as other sailors dropped from the high bunks onto him. Bodies would tangle and the big guns would fire. Then the screaming. Fighting for his boots, becoming entangled in his wife’s clothing pulled down around him as he lay in the closet next to their bed, head ringing from pitching into the back of their closet and from the screams of his terrified wife.

I find myself ruminating about all of the different ways my PTSD had impacted my first marriage leading to its final dissolution. My wife at the time had suffered at my hands. I find myself sinking into despondency and can’t work. I experiment shaking myself out of it, doing the fast-breathing exercise, and listening to some up-beat music. I clear my head, and am able to proceed.

Why Write Difficult Material?

Why go there, you might ask, for what purpose? Why lift and turn over rocks, just to see anew what crawls out? Especially when there’s a strong likelihood that more will emerge, new things remembered? Good question, and one not so easily answered. As I wrote my personal, extreme experiences, I used to think I was showing off; dusting off the battle ribbons. Then it felt more like a confessional, a chance to throw light on my personal pitch-dark places. Now, perhaps with age, I am simply trying to make sense of the welter of confusing lived epiphanies—faster than seeing a shrink, better results. Yet I find that even beyond all that, more is involved. I’m beginning to sense that some larger process is afoot.

While writing a short memoir piece about a difficult encounter with a family (for the story “Revival Sunday” in Chaos & Ash2), I have trouble with sudden feelings of shame and guilt:

“What did you do in the war?” asked the young girl. No one in the family said anything and everyone studiously chewed their fried chicken. “Did you kill anyone?” she persisted. “Daddy did.” Everyone suddenly wanted the peas passed. Isn’t the gravy great? I mumbled something, seeing vaporous souls rising out of the shoreline jungle. No one really knew what to say after that. I could hear the artillery in the distance. The arc light shells flood the midnight shoreline of the jungle with silver light and black shadows. The boat rocks as we drift, waiting.

Finding myself unable to avoid several similar memories, I get up and take a quick run. During my several circuits of the nearby park, I realize that I need to call Al, my friend from the ship with whom I’ve stayed in touch. Al always seems to help me sort things out.

I don’t write to shock, and am sensitive to the well-being of my readers. If I am going to tell stories that are difficult to write and to read, then there must be a good reason to do so. It is often said that these are times of darkness. Political disquiet in the face of monumental climate collapse, the loss of the familiar, uncertainties of headlong change, all point to a widespread need for reasons to persist.

Many writers these days seem to write to shock, or entertain through extolling violence and pain. I find that totally irresponsible. I hope that I can pull from my own experience in such a way as to touch upon the revelations of human experience amidst the vagaries of the world. I look for the fireflies in the darkness that suggest possibilities of hope.

Going Deeper

We all have lived plot-twists that proved to be epiphanies, or even everyday moments that, when examined, glow from within. Whether we write fiction, nonfiction, or poetry, as writers we pull from our deep wells, and try to put those moments into words that convey significance and meaning. Yet sometimes in the retelling, they pull from us unexpected blow-back: we become blocked or paralyzed, or we find ourselves overwhelmed by memories or wild imaginings. We are tempted to back away from those memories; sometimes we are driven away by fear and revulsion, by what they reveal about our deeper selves. With some focused self-care, we can go even deeper into that which we find difficult.

In Part 3 of this essay, I will look at how Form can help us regulate distance while we write personally difficult material.*

Reference Notes:

- Johnson, Kendall. Black Box Poetics (Bamboo Dart Press: 2021).

- ---. Chaos & Ash (Pelekinesis: 2020).

- The diagram Individual Response Levels was developed and modified by Kendall Johnson during more than 20 years of consulting for emergency service agencies and the military, and has been published previously in books, journals, and training guides.

*Publisher’s Notes:

Part 3 of this Writing to Heal series is scheduled to appear in Issue 18 of MacQ on the first of May, 2023.

Part 1, “Tapping Hidden Gifts of Experience,” was published in Issue 16 on New Year’s Day.

Here in Issue 17, you can also find Kendall Johnson’s conversation with Tony Barnstone, prize-winning poet, scholar, and author of Tongue of War: From Pearl Harbor to Nagasaki, as Barnstone shares his perspectives about writing personally difficult material.

Kendall Johnson

grew up in the lemon groves in Southern California, raised by assorted coyotes and bobcats. A former firefighter with military experience, he served as traumatic stress therapist and crisis consultant—often in the field. A nationally certified teacher, he taught art and writing, served as a gallery director, and still serves on the board of the Sasse Museum of Art, for whom he authored the museum books Fragments: An Archeology of Memory (2017), an attempt to use art and writing to retrieve lost memories of combat, and Dear Vincent: A Psychologist Turned Artist Writes Back to Van Gogh (2020). He holds national board certification as an art teacher for adolescent to young adults.

Recently, Dr. Johnson retired from teaching and clinical work to pursue painting, photography, and writing full time. In that capacity he has written five literary books of artwork and poetry, and one in art history. His memoir collection, Chaos & Ash, was released from Pelekinesis in 2020; his Black Box Poetics from Bamboo Dart Press in 2021; The Stardust Mirage from Cholla Needles Press in 2022; and his Fireflies Against Darkness and More Fireflies series from Arroyo Seco Press in 2021 and 2022.

His shorter work has appeared in Literary Hub, Chiron Review, Shark Reef, Cultural Weekly, and Quarks Ediciones Digitales, and was translated into Chinese by Poetry Hall: A Chinese and English Bi-Lingual Journal. He serves as contributing editor for the Journal of Radical Wonder.

Author’s website: www.layeredmeaning.com

More on the Web: By, About, and Beyond

⚡ Kendall Johnson’s Black Box Poetics is out today on Bamboo Dart Press, an interview by Dennis Callaci in Shrimper Records blog (10 June 2021)

⚡ Self Portraits: A Review of Kendall Johnson’s Dear Vincent, by Trevor Losh-Johnson in The Ekphrastic Review (6 March 2020)

⚡ On the Ground Fighting a New American Wildfire by Kendall Johnson at Literary Hub (12 August 2020), a selection from his memoir collection Chaos & Ash (Pelekinesis, 2020)

⚡ A review of Chaos & Ash by John Brantingham in Tears in the Fence (2 January 2021)

| Copyright © 2019-2026 by MacQueen’s Quinterly and by those whose works appear here. | |

| Logo and website designed and built by Clare MacQueen; copyrighted © 2019-2026. | |

|

Data collection, storage, assimilation, or interpretation of this publication, in whole or in part, for the purpose of AI training are expressly forbidden, no exceptions. |

At MacQ, we take your privacy seriously. We do not collect, sell, rent, or exchange your name and email address, or any other information about you, to third parties for marketing purposes. When you contact us, we will use your name and email address only in order to respond to your questions, comments, etc.