|

|

|

|

|

| Issue 14: | August 2022 |

| Nonfiction: | 3,332 words [R] |

| + Footnotes: | 73 words |

By Kate Flannery

Reaping the Whirlwind: An Interview with

Kendall Johnson and John Brantingham

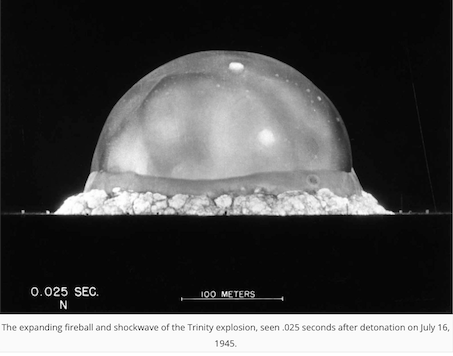

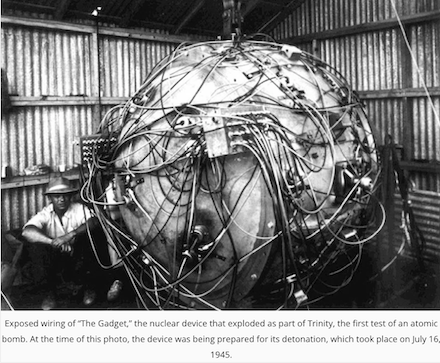

July 16, 2018 marks another anniversary of the first atomic bomb test, which took place about 230 miles south of Los Alamos, New Mexico. Not everyone will be celebrating the event. Kendall Johnson, a seasoned psychotherapist, artist, and writer, and John Brantingham, a poet laureate and professor of literature, are two of those who think it would be better to consider thoughtfully what was really accomplished on that day in 1945.

Robert Oppenheimer, often referred to as “the father of the atomic bomb” and head of The Los Alamos Laboratory at the time, said later that watching the first explosion and now-iconic mushroom cloud brought to mind words from the Bhagavad Gita, part of Hindu scripture: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” He soon became a fierce advocate for the control of nuclear weapons.

In poetry and in paintings, A Sublime and Tragic Dance gives us a renewed and vivid awareness of the destructive force released in 1945 as a result of Oppenheimer’s and others’ work on The Manhattan Project.

The following conversation highlights some of the thinking of Kendall Johnson and John Brantingham regarding this book and its timely subject.

Kate Flannery: The story of how you two met and started working together on this project is an interesting one: a mixture of chance, shared energies, and shared concerns. How did this all begin, and will you continue to collaborate in the future?

Ken Johnson: I first met John on one evening in January, 2017. I was at the dA Center for the Arts in Pomona to sit an exhibit of my works on Vietnam. My exhibit included writing fragments that accompanied the works. I went downstairs to the gallery and found it filled with poets—a group from the San Gabriel Valley Literary Festival—who were having their monthly poetry reading. John was their leader. John asked me to join in their session and read my exhibit’s writing fragments. He also asked me to join them afterwards for beer at a nearby Vietnamese restaurant. By the time we were finished I was hooked. A week later we met again and the subject of J. Robert Oppenheimer came up.

We both found Oppenheimer fascinating as a character; we also saw his work as terrible and sublime in both vision and scope. As we talked, we looked over some of my paintings and decided to work together on a project focusing on Oppenheimer and his work. We laid out a series from my collection and the conversation began. One of John’s favorite poetry forms is ekphrastic poetry, so the project seemed a natural one. At first I was going to provide only the images and he the ekphrastic poetry. But as things progressed I became involved in the writing aspect of the work, and so our project morphed into a new collaboration, ultimately resulting in this book. Hopefully this will be only the first of more collaborations to come.

John Brantingham: Yeah, it was incredible to be allowed to look at all of Ken’s paintings in his studio. I was given a view of the artist that few people have. From that, I saw the complexity of his mind and how that could add a layer to my understanding of a topic such as Oppenheimer. I love to work in collaboration with other people, because that collaboration inevitably leads me to new perspectives on the subject matter. In essence, I’m not caught up in whatever shortcomings I have. Working with Ken has been great, because we have similar opinions and ideas but come from completely different experiences. Working with someone who is a visual artist gave me a way of rethinking the topic.

KF: What drew each of you to want to study and write about Robert Oppenheimer? What was it in his character or his soul that made you want to dig more deeply into his story?

KJ: I find Oppie (a nickname he received when at University of Leiden to study with a colleague of Einstein) the prototypical Modern Man—cut off from his own world and having difficulty understanding the effects of his actions on others. He grew up in the privileged upper middle class of New York City; he was coddled as a child, attended exclusive private schools, and allowed to remain aloof from children his own age. His parents allowed him his eccentricities and encouraged his quirks which only led to more isolation. In college he had great difficulties socially, although his brilliance was apparent. Graduate school was worse. It wasn’t until post-doctoral study in Germany that he began to collaborate with others in any meaningful way, and then it was with the superstars of his day. The Manhattan Project was his chance for ultimate professional affirmation. In a sense, I think it represented a kind of atonement for his previous isolation, a reconciliation with others. And yet at some point he chose to go ahead with a project which he knew would be used against civilians and was morally problematic. It was a character-defining situation and he swallowed his qualms. I figure it was for the glory.

JB: My reaction is similar to Ken’s in a lot of ways. Discussion of Oppenheimer is often complex, which I find refreshing. His biographers have had a hard time deciding who he is, and I think that’s appropriate. I haven’t come to any clear decision about who he was either. Too often we oversimplify people and what their lives mean. People are neither wholly good nor evil. They are people. Of course, I can point to rare individuals and say, yes, that person was evil, but on the whole there is a mix. Oppenheimer invented what may prove to be the world killer, and the motivations behind what he did probably include ego, a will to power, fear, a genuine desire to protect troops, a need to stop Nazism, and probably a hundred other things. I agree completely about what Ken says about the glory and about his qualms. It is those qualms that fascinate me.

Another reason I wanted to write about him is that the nuclear dread that has been napping inside of me since the late Eighties is now waking up due to recent political events, and I wanted to confront it: understand it and understand how I am going to live in this new reality. I had a severe case of that dread growing up. If I am going to die in a flame that devours my civilization, I want to understand how we got to that place at least. Is that too dramatic? Possibly it is.

KJ: John speaks of dread. I grew up during the ’50s, before our country had become anesthetized to the idea of nuclear warfare. Our political concerns in the ’60s and ’70s became more current as time went on, and the trope of “nuclear fear” fell out of fashion in favor of clamor in the streets. Then after the ’70s, it became a matter of societal memory loss. But now it’s back. Not that it ever really went away, of course, but media and public attention are now shifting back to the dangers of nuclear war. John is smarter and more aware than most, so he grew up with nuclear dread when it played a subdominant cultural melody. That dread has recently been reawakened. With me it was terrifying then in the ’50s, and it always has been.

KF: It was Oppenheimer who chose the codename “Trinity” for the first test of an atomic bomb. “Trinity” was a reference to one of John Donne’s “holy sonnets” which begins, “Batter my heart, three person’d God....” The poet goes on to call upon God to transform him, by violent means, toward goodness. What do you think about Oppenheimer’s choice of this name for such a momentous and horrendous event in our history?

JB: I think he often used the religious in such a way to suggest that he was in some way god-like. In his famous quotation from the Bhagavad-Gita, “Now, I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds,” I think he was taking on the mantle not of the prince, but of Vishnu, the god. In John Donne’s “Trinity,” it is God who is doing the battering. In the Trinity Test, it was Oppenheimer. One way of understanding this is that Oppenheimer was wrestling with what it means to take on god-like powers. Another way of understanding it is that he was glorying in taking on those powers. However you understand it, he spent his life fascinated by the elemental and mythic powers of the universe. While living in the desert, he would ride his horse out into lightning storms for the pleasure of feeling the power of the sky. He studied ancient scriptures. I think these forces led him to his deep understanding of physics.

KJ: I agree. I also think the Oppenheimer tale is a target-rich environment if you’re looking for contradiction and confusion. Mysteries abound. In many ways he had the character of a mystic, and when you think about the rudiments of particle theory, how could he not? If matter consists of emptiness and a few specks of energy, where does pain come from? Or joy? The world that he inhabited was the epitome of instability. Yet something cohered it all for him. He had some vision that pulled order out of apparent chaos, some lodestone more than simple trust in a hypothetical natural law. Some might call that God. I hunger, we all hunger for such a vision. We all seek something that makes it all make sense. Whatever his understanding of physics, he nevertheless swam in a mythopoetic sea. I think he used that language when it captured the multiplicity of the moment.

KF: As you worked together and learned more about Oppenheimer, what do you consider to be the important things that you discovered about him as a human being and as a scientist, a man of reason?

JB: I was struck by how unreasonable he was. It’s said that he attempted murder twice in his life although he was never charged with a crime. Once, in a moment of symbolic evil he poisoned an apple. I was surprised by these kinds of acts, because I had grown up with an image of him as a staid and reasonable person, doing things out of a conception of the world that required a view to the greater good. In the end, I came to the belief that the man was a mixture of motivations. But that’s what it means to be a human. In the end, I saw him through the lens of humanity instead of in the oversimplified way we like to see people of the past.

KJ: Yeah, I agree. The man embodied more contradiction than ten of the best of us. He was complex and very vulnerable. He could take the lead in a massive, groundbreaking project, knocking heads with military and security people, and then be crushed when he was later discredited. He could see the world as described by Hindu prophets—all fire and change—and yet be baffled by people who saw things differently. He could develop a weapon that killed two hundred thousand souls in two strikes and yet find a bigger version of that weapon to be an abomination.

KF: As you put this volume together, choosing which art and which poems to use, what direction did you want the art and the poetry to take? How did you decide what you wanted in the flow of the work?

KJ: The artwork was complete when we began but existed largely as separate pieces rather than a series. John was especially helpful in seeing the continuity and development of theme as he and I ordered the series. Once that initial ordering was complete the meanings latent in each began to speak to us. Then John began writing. I became so excited by his work that I was soon contributing poetry to our common folder.

JB: I love working in collaboration. The first word was always Ken’s, because we were working from his paintings. However, after I started writing, and he started responding, we began to have a real conversation about the nature of the man and our world. We talked one-on-one and through our art. We talked online and read similar books. I watched a lot of documentaries and found an old Person to Person program where Edward R. Murrow interviewed Oppenheimer. Ken and I went over all of this until we found that we had the beginnings of an understanding of him. You can never completely understand anyone, even yourself, but this collaboration led us more deeply into ourselves.

KF: Ekphrastic poetry has been described as “poetry confronting art.” Your book seems to be more than that. The poetry and the art seem to complement each other rather than to confront. If I’m correct in this, did you have this in mind when you began working together or did it evolve over time?

KJ: The words “confronting” vs “complementing” are interesting choices. Ekphrastic poetry is often written following a visit to a museum or studio, where the writer is challenged by the work to rethink things and make poetic sense of it. John is a specialist in ekphrasis and has written books about the process. I’ve been working on a couple of projects using writing as a way of deepening the viewer’s experience. I’ve admonished viewers not to assume that the artwork illustrates the writing, nor that the writing explains the artwork, but both—together—point beyond themselves. I think this cuts closer to the bone of this book, that our writing and the art pieces all speak together about a multifaceted character in a complex era: Oppenheimer and the decision to engage in nuclear warfare.

JB: Yeah, I’ve always viewed ekphrasis as part of a cultural conversation. The arts in general are a conversation we’ve been having for thousands of years, but ekphrasis is a direct discussion. Ken’s absolutely right. It’s not about illustrating poetry or explaining art. It’s a discussion, so this is as much responding to Ken’s poetry as it is about the art. I think I’m correct in saying that Ken is an abstract expressionist so he is often painting the emotion as opposed to illustrating the event. If I’m wrong about that, Ken, please correct me. So we’re often writing about these concepts on an emotional or even spiritual level rather than discussing events. After all, we have books and essays to do that.

KJ: For the most part, John is right in characterizing my painting as abstract expressionist in that the feeling is more important than figure or concept. I’d like to sharpen that a bit. As I work on a piece, a dialogue begins between me and the piece I’m working on. I push it—the materials—about, but the result speaks back, leading me off in new directions. While some artists start with a clear vision of the finished product, I learn and am transformed by my process. Sometimes I end up 180 degrees from where I started, and that is usually a good thing. It tends to be more, however, than simply emotion. Often I find I have been working on the background, context, implications, and metaphysics behind the emotion, much less than the figure.

That said, many of my paintings have been about one or two main themes: nuclear war and Vietnam. John helped me put the former into a better articulated series. I’m also finding that including the poetry—his and my own—helps delve into the content with greater depth and clarity.

KF: July 16th is the anniversary of the first atomic bomb test near Los Alamos, New Mexico. How do you believe we should be thinking about that day in 1945?

KJ: July 16th is the day we saw the culmination of the great race to build the bomb and were shown the consequences. It was a revelation. We saw the power we had harnessed. We also saw what we needed in order to make the decision about using it. August 6th and August 9th were the apocalypse. We knowingly used “Little Boy” and ”Fat Man” (the nicknames given to the two bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki)[1] to purposely incinerate and irradiate the better part of two large cities and their mostly civilian human population. The intentional firebombing of German and Japanese cities in the last part of the war showed that we as human beings are already fallen. July 16th revealed our capacity.

JB: I think that nuclear weapons were inevitable, given our human curiosity. Their use, however, was not inevitable, and I think we need to use days like July 16th, as well as August 6th and 9th, the days when the atomic bombs were first dropped on human populations, for moments of reflection. I am constantly amazed by people’s capacity for evil. I’m sometimes amazed by my own capacity for it. In reflection, I see that I gain nothing from it, and it makes everything, including my own life, much worse. Why do it then? Why purposely engage in something that is evil? We as humans have great power, and I believe that everyone is capable of ultimate evil. It seems to me that the only way to prevent a tragedy in our world, where those two things merge, is through reflection.

KF: That’s a good lead-in to my last question. Just two years before his death this year, renowned physicist, Stephen Hawking, echoed Oppenheimer’s sentiments about the development of nuclear weapons. Hawking added a slightly more optimistic twist: “Most of the threats we face come from the progress we’ve made in science and technology,” he said. “We are not going to stop making progress, or reverse it, so we must recognise the dangers and control them. I’m an optimist, and I believe we can.”[2] Do you agree?

JB: I think one thing we need to do in order to recognize and control those dangers is to stop seeing ourselves as a world of nations; we need to see ourselves as a world of people. Nationhood and the need to have power within and among nations is one thing that’s likely to lead to our destruction. Nine nations have nuclear weapons. All it will take to lead to a tragedy, the likes of which we have never seen, is for one leader of those nations to put the concept of nationhood, his or her own ego, or some kind of related, concocted philosophy before common sense and humanity.

KJ: Absolutely! Technology has developed life-saving drugs, ways to increase farm yield and decrease starvation, along with various forms of clean energy. On the other hand, nuclear threat, development of the machine gun, “star wars” technology, threats of Artificial Intelligence Technology going awry all show us the emergence of a new world that may not bode well for us. There is clear evidence that electronic toys, entertainment, and communication systems are changing our neural DNA and desensitizing us to the consequences of our actions. Hawking is right: the forces of marketing and economics are not going to make technology go away, and it’s up to us to control them and to control ourselves. Unfortunately, we don’t have a July 16th revelatory moment to make that as clear as it was in 1945.

|

A Sublime and Tragic Dance: Robert Oppenheimer & the Manhattan Project By Kendall Johnson and John Brantingham CreateSpace, 2018 Click image at left for details. |

—Interview published previously at Cholla Needles Arts & Literary Library (15 July 2018): appears here with permissions from Kate Flannery, Kendall Johnson, and John Brantingham.

Footnotes:

Links below were retrieved on 22 July 2022.

- The three black-and-white photographs above are from “The Trinity Test, the day the Nuclear Age began, 1945” at Rare Historical Photos (updated 12 November 2021):

https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/trinity-test-day-nuclear-age-began-1945/ - Quoted in Stephen Hawking Says a Planetary Disaster on Earth Is a “Near Certainty” by Peter Dockrill, Science Alert: The Best in Science News (20 January 2016).

Kate Flannery

is an Editor-at-Large for The Journal of Radical Wonder. She lives in a small college town in California where she also practices law. Her essays, poetry, and fiction have been published in Chiron Review, Emerge, Shark Reef, The Ekphrastic Review, and Pure Slush, as well as other literary journals.

She works regularly with the Sasse Museum in Pomona, California and has contributed to exhibition catalogs for the museum as well as writing ekphrastic poetry to the artwork on display there. Her writing for the museum has been featured in The Torso Project, Photography Past and Present, Icons, Nudes, and 14 Stations, among other Sasse publications.

She was a finalist in Bellingham Review’s 2022 Annie Dillard Award for Creative Nonfiction and is currently working on a curated volume about Palmer Canyon after the Grand Prix Fire of 2003.

More on the Web: By, About, and Beyond

⚡ Stargazers, a prose poem by Kate Flannery on page 52 of the e-book Starry, Starry Night: an ekphrastic anthology inspired by Van Gogh’s masterpiece, published by The Ekphrastic Review (25 February 2022)

⚡ Where Does the Anger Come From? (a prose poem) at Spillwords Press (11 October 2021)

| Copyright © 2019-2026 by MacQueen’s Quinterly and by those whose works appear here. | |

| Logo and website designed and built by Clare MacQueen; copyrighted © 2019-2026. | |

|

Data collection, storage, assimilation, or interpretation of this publication, in whole or in part, for the purpose of AI training are expressly forbidden, no exceptions. |

At MacQ, we take your privacy seriously. We do not collect, sell, rent, or exchange your name and email address, or any other information about you, to third parties for marketing purposes. When you contact us, we will use your name and email address only in order to respond to your questions, comments, etc.