|

|

|

|

|

| Issue 1: | January 2020 |

| Ekphrastic CNF: | 999 words |

| Visual Art: | Postcard |

By Pamela Johnson Parker

It’s a Hard Art, Living

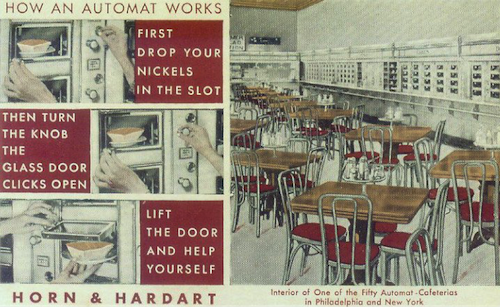

How an Automat Works

Horn & Hardart vintage postcard *

Fistful of nickels. Click of the door. Helping myself to the cornucopia inside.

I’m the only person I know who’s eaten at Horn & Hardart, out of business since early 1991. I sat there with Sam, my very first lover, in our fur coats in 1978, and planned out a relationship that would let him see other people (his idea—he was interested in men) and let me never have to work (my idea—I’d been working nearly nine years, since I was 12). I’d ironed shirts, changed sheets, folded towels, mopped floors, wheeled an old man onto his patio to feel the sun’s warmth on his face. I never wanted that again—to care for someone whose life was ending.

Five years later, when Sam was dying, I did those things for him—swabbed his floors, changed his pajamas, made sure his sheets had the highest thread count I could afford, wheeled him into the sunlight on the terrace of his hospice room, helped him stand when he couldn’t stand alone.

With him, the first time when I was 13 and he was 17, as we perfected sex. Technique, physique—we were each other’s perfect fit. Except for the fact that he liked boys and he didn’t tell me. And I liked him and didn’t know about gay. And his family liked me enough to give us everything two kids could possibly want—his grandmother’s diamond, a house, a car—if we’d marry. They thought that gay would be licensed, put away.

With him when I was nearly 19, two weeks before we were to stand under the chuppah his family insisted on, before we were to sleep under the canopy of the honeymoon suite of the Palmer in Chicago, before we were to lie under the stripes of a beach umbrella in Kingston; with him when he said, “I think we should see other guys.”

With him when he explained exactly what that entailed, when I told him I never wanted to see him again and threw his grandmother’s ring at him and left.

Without him when I realized those were the bravest words that could be said in 1975. (They’re still the bravest words I know). Without him when I figured out that I can’t was better than I do.

With him when he said, “Let’s try again. When we’re together, we’re together.” The other part of me. Terrific sex and crazy conversations, spontaneous trips to New York and the Russian Tea Room and CBGB, Montreal and Mount St. Helens, cross-coast moves to San Francisco. A year of peripatetic.

With him when I told him I could never have sex with him again, that sharing was too hard. With him when he told me, It would be you, if it could be you.

With him when he met his boyfriend. With him when his boyfriend left. With him when his last lover came into his life, and when his last lover slipped out of his hospital room, never returning.

With him when the first purple spot of Kaposi’s appeared, the center of Queen Anne’s Lace on his skin (a word I later learned as maculate). With him when the first curls fell out, like so many pencil shavings. Shaving his head when his vanity couldn’t stand thinning.

With him through vomit and blood, mouth blisters and meningitis.

With him as we’d never promised, for better, for worse. Not wedded but welded.

With him. He wasn’t alone. He didn’t die alone.

He left me. Left me with a garnet necklace, diamond earrings, an idea of what was and wasn’t love. Back then, who knew about HIV?

I was so lucky. Negative. The year before the virus hit Manhattan, our sex had become safe.

Without him, when he was with his first true love, when I met my first husband. I left technique behind and went for trouble: the most macho, motorcycle-riding badass I could find.

That was lust. And we paid for it. The only good from that marriage was my son and a ticket to California when Sam was dying. For that I’ll always love my first husband a tiny bit; he gave me that time.

Not love but generosity. But Sam? Sam was love. He was Horn & Hard Art. This living, this dying.

I swore after Sam that I’d die first, that no one else would ever die on me. I’m not, you see, a stranger to loss.

I lost my beloved grandmother, my birthstone ring, my St. Christopher’s medal.

I lost my true love, Harvey, whom I miss every day.

I don’t think of Sam every week, every month, every autumn. But today, I do: first love, best friend, kisser in the take-no-prisoners style that sent my latest lover reeling, who taught me about Art Deco and Art Carney, about Blondie and Baudelaire.

These days, when I find myself not only as widow—but also as writer, mother, teacher, and even partner again—I want to go back, to the future I’m supposed to have. I want to see Sam one more time, to introduce him to my children, to show him poems and peonies and Jacob’s coat roses, my Bakelite bracelets and blingiest rhinestone brooches. I want to walk for hours with him, talking nonstop. I want to brush his hair, have him brush mine. I want to hear him say, You’re still my best friend.

There’s one more thing I’d like to do with Sam, and I’m thinking of it today. That postcard, that ephemera, brought it back, that first love.

I want to have coffee with him at Horn & Hardart, scatter Sweet-N-Lo packets like wedding confetti on the table, have him throw them at me; fit a nickel into the sweet shell of his ear; laugh and look at him and lean back in one of those curved coffeeshop chairs, the ones with the evocative backs, the ones with the name I called Sam.

Sweetheart.

*Publisher’s Notes:

1. Postcard photograph of Horn & Hardart Automat depicts how the automated cafeteria

worked, by Lumitone Photography, New York, circa 1940s. This photo is in the public

domain in the United States because it was produced in the USA for public distribution

between 1924 and 1977 without a copyright notice. Image above was downloaded from

Wikimedia.

2. King of fast-food restaurants for nearly a century, Horn & Hardart opened its

first Automat Cafeteria in July 1902 and closed the last one in April 1991. For a brief

history, see the short film by slideshow director Alan G. Wasenius on YouTube,

Just Drop it

in the Slot; a Look at the Horn and Hardart Automat and its Legacy.

Pamela Johnson Parker

is the author of a collection of poetry, Cleave, which won the Trio Award from Trio House Press, and two chapbooks: Other Four-Letter Words (Finishing Line Press, 2009); and A Walk through the Memory Palace (Phoenicia Press, 2009), which won the Qaartsiluni Chapbook Prize. Her flash fiction, poems, and lyric essays have appeared in journals such as Iron Horse Literary Review, New Madrid, American Poetry Journal, diode, Anti-, Poets and Artists, Gamut, Spaces, and Muscadine Lines: A Journal of the South. Her work has also been featured in the anthologies Language Lessons: Volume 1 (Third Man Press), Poets on Painting, The Rivers Anthology, and Best New Poets 2011 (judged by D.A. Powell).

In 2018, Parker won an Al Smith Fellowship from the Kentucky Arts Council, and her work was nominated for the Pushcart Prize and two other awards, Best of the Net and Best American Science and Nature Writing. She received her MFA from Murray State University in western Kentucky, where she taught humanities, creative writing, contemporary poetry, and forms of fiction before transferring to the Department of Art & Design. Her novel manuscript, Horn & Hardart, is currently making the rounds.

More on the Web: By, About, and Beyond

⚡ What I Told the Jehovah’s Witnesses and Why They’ll Never Be Back in KYSO Flash (Issue 11, Spring 2019); this lyric CNF is on our publisher’s list of 100 Faves Published in KYSO Flash.

| Copyright © 2019-2026 by MacQueen’s Quinterly and by those whose works appear here. | |

| Logo and website designed and built by Clare MacQueen; copyrighted © 2019-2026. | |

|

Data collection, storage, assimilation, or interpretation of this publication, in whole or in part, for the purpose of AI training are expressly forbidden, no exceptions. |

At MacQ, we take your privacy seriously. We do not collect, sell, rent, or exchange your name and email address, or any other information about you, to third parties for marketing purposes. When you contact us, we will use your name and email address only in order to respond to your questions, comments, etc.